In a nutshell

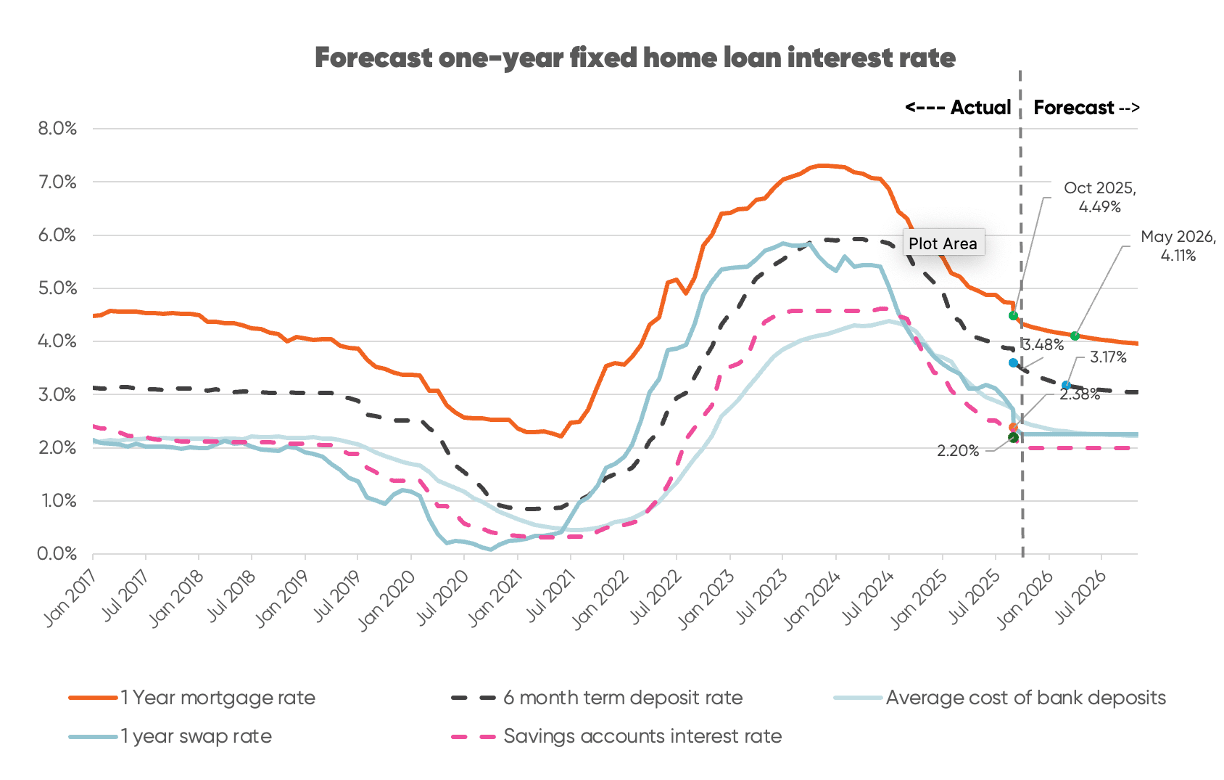

- If the OCR eases to 2.25% in late November, it’s likely we’ll see the one-year fixed mortgage interest rate fall to (just) below 4% in early 2026.

- This conclusion is based on Squirrel’s modelling of Reserve Bank-sourced retail and wholesale interest rates over the last eight years*.

- The catalyst for further reductions will be the banks continuing to lower their term deposit interest rates, and the gradual flow-through to lower overall bank funding costs.

- The model forecasts the one-year fixed home loan rate will decline to around 4.1% in early 2026. Our experience indicates that, sooner or later, a bank won’t be able to resist offering a headline rate of 3.99%.

* The forecast was derived using an ARIMAX(1,0,0) time-series model trained on historical periods of falling interest rates, with the average cost of bank deposits and the 1-year swap rate as exogenous predictors.

How looking back can help us to predict the future

You have to remember that, in New Zealand, our banks are answerable—first and foremost—to their (largely) overseas shareholders.

The ultimate goal is always maximising profits.

Now, if there’s any upside to that at all from a customer perspective, it’s that it makes the banks fairly predictable in terms of how they respond to movements in interest rates. At the end of the day, they’ve got to protect their underlying margins.

As a rule, they also always tend to move together (which is typical of an oligopoly)—although there will be leads and lags, of course, which vary depending on whether interest rates are going up or down.

Using historical wholesale interest rate data from the Reserve Bank, spanning the last eight years, we’ve built an AI model to help us predict where retail interest rates might end up in the event of future OCR cuts.

Looking backwards—the outputs of the model are pretty consistent with what we’ve seen in reality, in terms of how wholesale rates fluctuations have flowed through to actual mortgage rates in market.

Looking ahead—and assuming economists (and the wider market) are right in thinking the OCR will drop to 2.25% in late November—the model shows that we’re likely headed for a sub-4% one-year fixed mortgage rate sometime early next year.

How do we know?

There are a few key factors which play into what happens with the one-year fixed home loan rate.

Firstly, there’s the one-year wholesale interest rate a.k.a. the swap rate.

Since it’s quite short-term, it essentially reflects what the markets expect the average Official Cash Rate (OCR) to be over the next 12 months. As this one-year swap rate rises and falls, the one-year fixed home loan rate typically follows suit.

Secondly, there’s the cost of deposits that banks hold from households and business customers.

The banks, rather than the wholesale markets, set these rates, but they’re always heavily influenced by both the OCR and other short-term wholesale interest rates (from 3 months up to 12 months).

These bank deposits fall into three categories:

- Transaction account balances—currently at $130 billion, with $40 billion from Kiwi households (and generally earning zero interest).

- Savings account balances—currently totalling $115 billion, with $80 billion from households, most of which is earning between 0.05% and 2.5% (and earning an average of 1.7% before our latest 0.5% OCR cut).

- Term deposit balances—approximately $230 billion today, with nearly $150 billion from households. These deposits have fixed terms, mostly ranging from three months to one year. The interest rate is locked in, so it takes some time for the entire portfolio of bank term deposits to ‘reprice’ — i.e. to adjust based on a higher or lower OCR.

Term deposits are the biggie in this mix, making up about 50% of bank deposits, and the interest rate usually moves in line with wholesale interest rates.

Over the past eight years, data from the RBNZ shows an average margin of +0.7 % between wholesale interest rates and the six-month term deposit rate.

This means that banks, on average, pay retail customers more than they pay wholesale customers.

Back to the modelling

What we’ve done is input all those historical actual interest rates and forecast wholesale interest rates—based on a 2.25% OCR in late November—and asked our AI model to predict what will happen with savings account interest rates, term deposit rates, and the overall cost of bank deposits through to December 2026.

Then we’ve taken the overall cost of bank deposits and the one-year swap rate, and forecasted where the one-year fixed home loan rate will land.

The answer is a one-year fixed home loan rate just above 4% in early 2026.

So why is 3.99% our pick?

Like many retailers, banks love a price that ends in “.99”.

It’s a psychological tactic called ‘charm pricing’—which says that, at a glance, 3.99% sounds like a far better deal than 4.00%.

We reckon that if the one-year mortgage rate drops close to 4.00%, sooner or later one of the banks will want to claim bragging rights to a rate below 4.00%.

And then, before you can say ‘oligopoly’, every other bank will follow,

As for the term, although several banks currently offer both one- and two-year fixed interest rates at 4.49%, we believe that if the OCR is cut to 2.25% in November, economists will start to worry about when the Reserve Bank might raise the OCR.

This will keep the two-year rate higher than the one-year rate.

We saw this post-COVID when the one-year fixed home loan rate got down to a low of 2.1%, while, at the time, the two-year rate was 2.5%.

A sub-4% mortgage rate would be good for the economy

The New Zealand economy has been pretty stuffed for the last two years. And that’s putting it mildly.

From a global perspective, it’s lonely having a shrinking economy. Most western countries have managed to remain in positive economic growth territory even as they’ve fought (and won) the battle against inflation.

Squirrel’s view is that the Reserve Bank seriously overdid things in hiking interest rates in order to get inflation back down to its target band, and we’ve been vocal with that view for more than two years.

What the Reserve Bank lacked was patience, and in doing so, they pushed the OCR too high without allowing time for the OCR increases to flow through to the real economy.

Would a sub-4% mortgage rate re-ignite inflation?

Our view is no. Instead, we’d argue that it would create the environment for a steady economic recovery.

Three years ago, Kiwi homeowners were paying an average rate of 3% on their mortgages. Even with the forecast changes in interest rates, the rate in 2026 will still be nearer 4.5%.

That’s not low enough to ignite a mad dash to spend, and push up inflation in the process.

It might sound strange coming from a company like Squirrel—where the housing market is our bread and butter—but the best scenario for our country is one where we aren’t constantly (and completely) obsessed with interest rates and house prices.

A bit of stability is just what we need—giving us all room to go about the business of rebuilding our battered economy.

About the author: David Cunningham, Chief Squirrel

With more than three decades of senior experience across New Zealand’s financial services sector, David knows the world of banking and finance inside out. He's not afraid to call it like he sees it (all part of our fight for a fairer financial system) which is why he's a regular media commentator on matters relating to the economy, housing market, mortgages, saving and investing, and interest rates.