In a nutshell:

- New Zealand house prices have fallen 17% on average over the last three years, and well over 20% in Auckland and Wellington.

- In ‘normal’ times this would be considered a housing crisis of massive proportions—but the last five years have been anything but ‘normal’.

- Post-COVID, house prices rose about 45%, so the subsequent fall in prices still leaves prices above where they were in early 2020.

- Most Kiwi still have a job (RBNZ Governor Orr excepted), and their pay has increased significantly since 2020. This means that despite the fall in house prices and the dramatic increase in interest rates, most households have (with a bit of belt tightening) still been able to keep up with mortgage payments.

- At the margin, those who bought at the top of the market hurt the most. But most homeowners have ridden the price rise and drop.

- Banks don’t ‘call-in’ a loan so long as the mortgage payments continue – even if there is negative equity (ie. the size of the home loan exceeds the value of the house).

- Together, these factors have sheltered New Zealand from a housing crisis.

House prices have plunged

If, at any point over the last few decades, you’d told people that New Zealand house prices were set to drop by almost 20% in the coming years, the news would have felt almost catastrophic.

Homeowners would have been horrified. Bankers, with their huge home loan portfolios, would have been sweating at the thought. The Reserve Bank and ratings agencies would have been frantically running the numbers to work out whether our financial system could survive such a massive hit. Even the government would have been worried—falling house prices almost always lose elections.

Yet that’s exactly what’s happened in the last three years, and the world hasn’t ended.

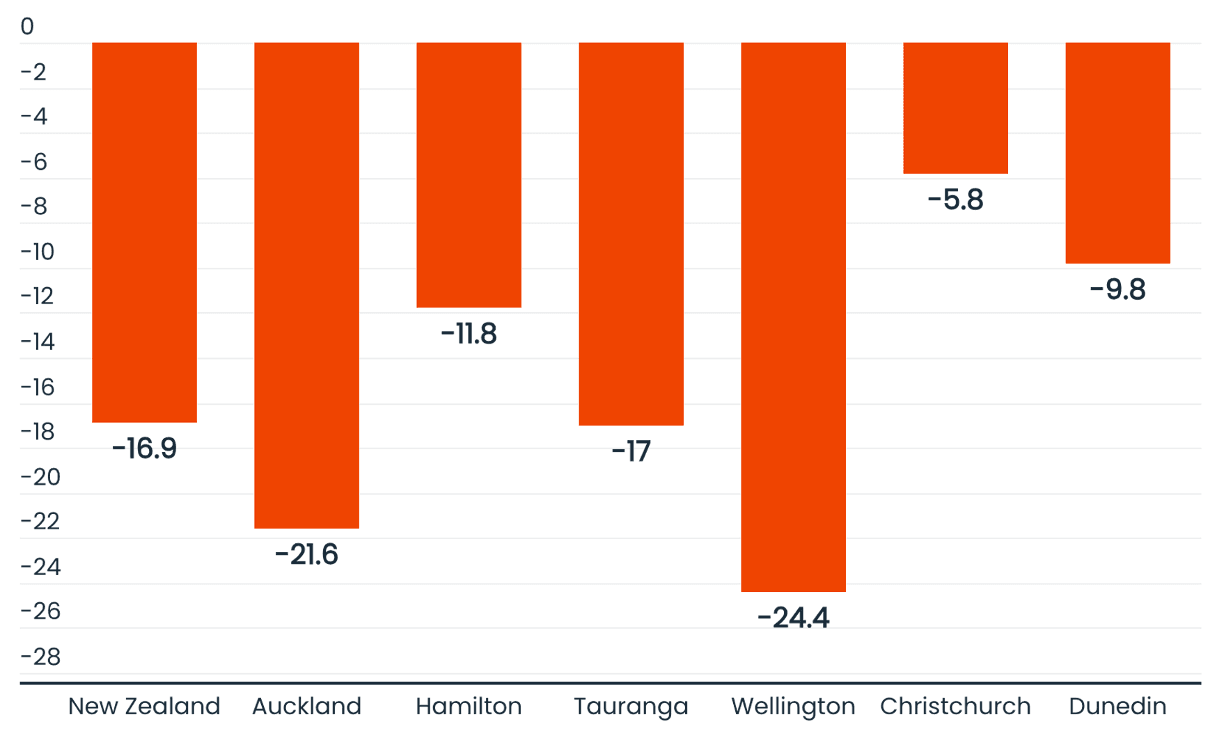

On average, New Zealand house prices have fallen 17% over the last three years. Some major centres have been hit even harder—with Auckland down 22%, and Wellington down 24%.

There’s no denying the picture isn’t pretty—but we’re still standing. In fact, there’s barely been a ripple of reaction.

So why is that?

To explain, we need to look at the situation from the banks’ perspective

When it comes to new mortgage lending, banks have a rule which says they’ll typically only lend up to 80% of a home’s value. This is what’s known as the loan-to-value ratio, or LVR.

In simple terms, this LVR benchmark is designed as a ‘buffer’ to protect lenders should a loan go bad. It means that—even if house prices were to drop quite a bit—the customer (or potentially the bank) could sell the property and recover the debt.

Your LVR falls naturally over time—as you chip away at your mortgage payments, and as house prices rise (which they have for decades in New Zealand) you build up more equity. People who have been in their home for a while, or who are moving house, tend to have lower LVRs.

In banking lingo, this is called “seasoning”. Not to be confused with the stuff you put on your steak, “seasoning” is just the idea that, as time passes, the loan carries less risk to your lender.

When house prices fall significantly, though—pushing LVRs upwards—some borrowers are left in a scenario where the sale price of their home is less than their remaining debt

Throw in a dramatic rise in unemployment, where borrowers are left unable to make the required payment on their home loan, and the downward price spiral becomes self-fulfilling.

More and more properties come onto the market, and sellers have to accept lower and lower prices.

That’s exactly what happened after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC)—house prices were suppressed for several years and levels of new home construction fell off a cliff, which in turn meant there weren’t enough homes for Kiwi to live in.

It took years for New Zealand housing supply to recover.

Banks regularly model the impact of big potential economic shocks

In fact, the Reserve Bank requires them to, as part of its remit to ensure that—should the worst happen—New Zealand’s financial system is strong and stable enough to ride out the storm.

The two main things the banks are concerned with are:

- Capital levels—i.e. do they have enough capital on hand to survive the shock?

- Customer confidence—i.e. will people still feel comfortable leaving their savings and investments with the banks?

Back when I was in banking, the sorts of scenarios we modelled included a foot-and-mouth disease outbreak hitting our agricultural sector, a COVID resurgence, climate change shocks such as a prolonged drought, or other large-scale events that disrupt the economy.

The good news is that the high levels of capital held by banks could withstand the modelled shocks, including some fairly extreme impacts such as a plunge in house prices.

So, does this latest fall in house prices mean we’re headed for a repeat of the GFC?

In short, no—the reason being that, before house prices took their latest plunge, they’d actually risen by about 45%.

Demand for property surged massively in the 18 months post-COVID, largely driven by generationally low home loan interest rates, which got down to close to 2% for a one-year fixed rate and to 2.99% for a five-year fixed interest rate.

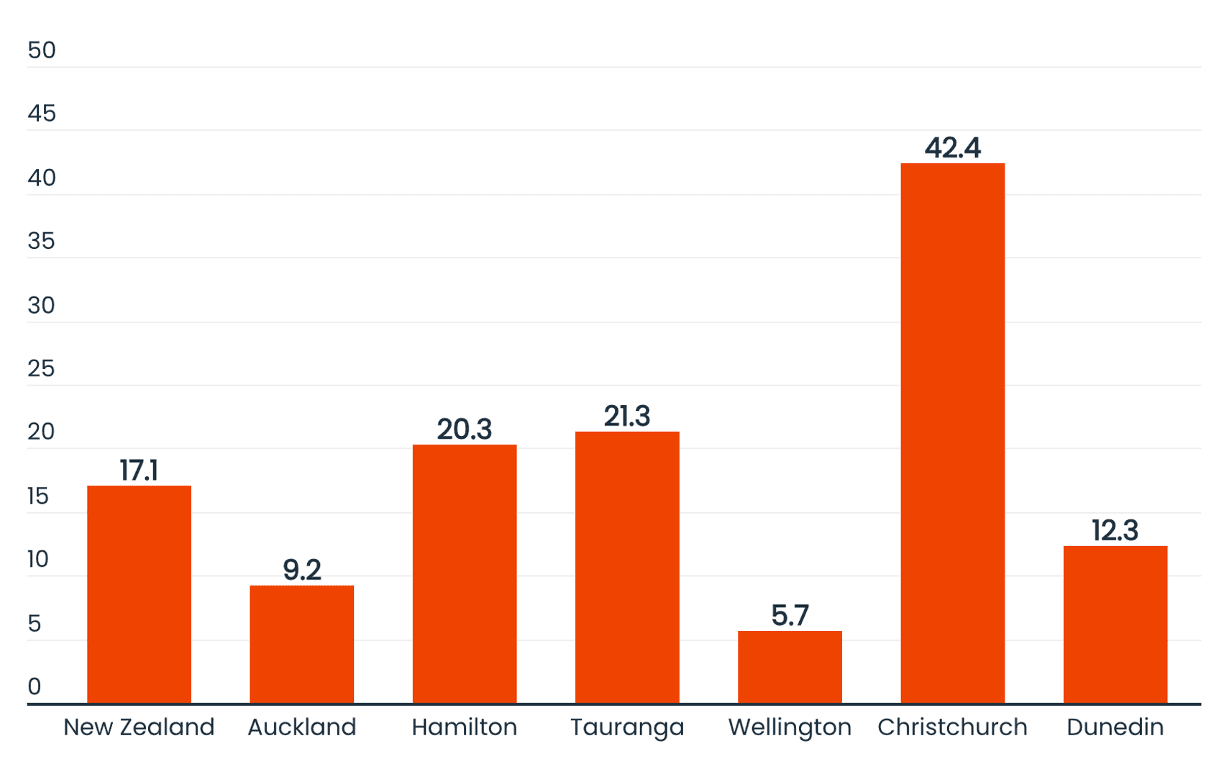

Once you factor that massive period of price appreciation into the mix, this is what today’s house prices look like compared to pre-COVID levels:

Even in the worst-performing markets—i.e. Auckland and Wellington—house prices are higher than they were at the start of 2020. In Christchurch, prices are up by an extraordinary 42%!

In other words, anyone who owned a home pre-COVID (or who sold and bought simultaneously post-COVID) is better off. Even in Wellington.

The exception will be first-home buyers who bought near the top of the market—whose equity in their home will now be low or possibly even negative. Factor in the subsequent 5% increase in interest rates (from round 2.5% to a peak of almost 7.5%), and it hurts.

But even then, there are ‘redeeming’ factors.

Inflation has driven significant salary growth in recent years—in many cases by as much as 20%—which (along with a bit of belt tightening) has helped make it possible for people to keep paying their mortgages.

With interest rates on the way down again, and most of us now rolling off onto lower rates, many people are through that pain, with further relief to come throughout 2025.

The curve-ball: unemployment

Despite the recession New Zealand experienced in 2024, employment has remained comparatively strong.

So, while the latest data shows that mortgage arrears are rising, the numbers are still relatively low. That’s because, if you have a job, you typically find a way to tighten your belt to make your mortgage payments—and most homeowners still have jobs.

Unemployment is likely to rise slightly over the first half of 2025, but it is off the low post-COVID base. Firms are still very reluctant to shed staff, having experienced post-COVID staff shortages before the surge in immigration over 2023/24.

Yes, more businesses are struggling, but there’s light at the end of the tunnel with the fall in interest rates lifting the economy out of recession this year.

Summing it all up

House prices have plunged in many of our major cities over the last couple of years, at the same time as interest rates have dramatically increased.

But taking a five-year perspective, Kiwi homeowners are in good shape with house prices higher than they were at the start of 2020, interest rates now falling, and unemployment only rising modestly.

In short, the plunge in house prices is not a crisis, and there is light at the end of the tunnel for homeowners with interest rates on the way back down.

Furthermore, Squirrel’s view is that we’ll see modest increases in house prices (around 3% to 5% per annum) over the next couple of years.

Combined, that will leave us all feeling a lot better off.

Footnote: what if this happened in the United States?

If something like this were to play out in the US, it’d be a totally different story.

That’s because US borrowers have the option to simply hand their keys back to the bank and walk away from the loan. If my house is worth less than the size of my loan, I can simply mail the keys to the bank, and I’ll be better off!

The higher the LVR when the loan is taken out, the more likely this is to happen—with the having potentially massive implications for the US, and even global economy.

This is broadly what happened in 2007 – 2008, triggering a global recession, a.k.a. the GFC.