The Reserve Bank (RBNZ) introduced debt-to-income limits (DTIs) on new bank mortgages in July—as a measure to help control future house price booms, and protect borrowers from going into financial distress in a rising interest rate environment.

While DTIs will bite well before prices increase like they did after the first Covid lockdown—and will make future booms much tamer than past ones—there can still be sizeable increases in house prices before they bite.

According to the RBNZ…

"The new DTI rules will allow banks to lend:

- 20% of owner-occupier lending to borrowers with a DTI ratio greater than 6

- 20% of investor loans to investors with a DTI ratio greater than 7.”

The primary focus of the new rules is first home buyers, because loans to them will be to buy houses.

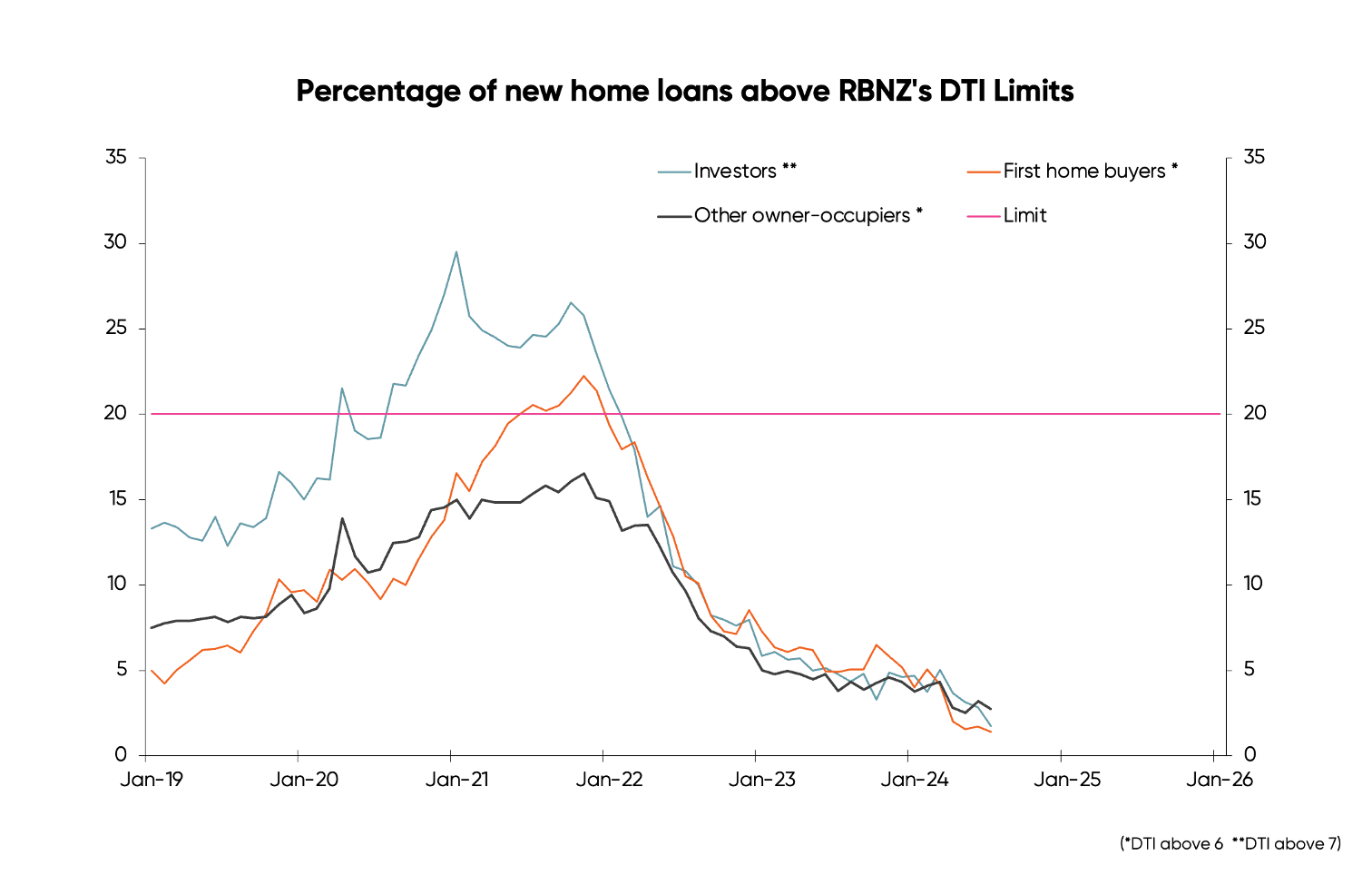

In July, high-DTI lending was low relative to the RBNZ’s 20% limits for the three groups: 1.4% of first home buyers above a DTI of 6, 2.7% of other owner-occupiers above 6, and 1.7% of investors above 7 (see first chart below).

This buffer implies significant room for house prices to increase before DTIs bite.

The first question is, will DTIs stop the sort of house price boom that occurred after the first Covid lockdown, when REINZ’s NZ House Price Index rose 44% in 18 months?

Well, they should, but not before a reasonable increase in prices.

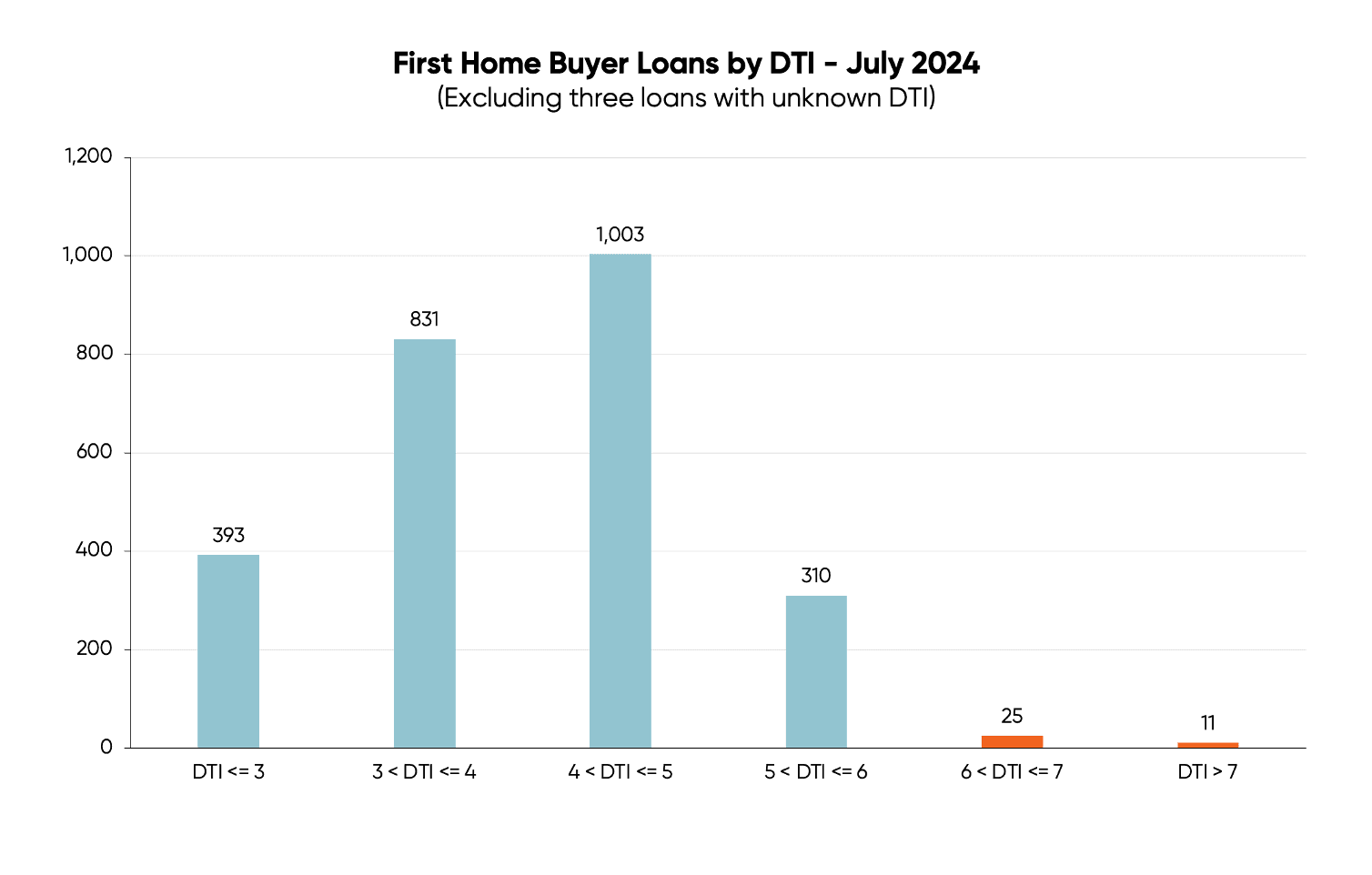

To demonstrate, the second chart shows the breakdown of the number of new loans to first home buyers in July, based on DTIs. Only 36 of a total 2,573 loans were classed as “high-DTI”—i.e. above the owner-occupier DTI of 6. The RBNZ’s 20% limit would allow for up to 515 of these loans to be high-DTI .

Assuming incomes stay flat, I estimate that the average house price can increase around 25% before the 20% DTI limits were reached for first home buyers.

That provides a static estimate of how much headroom there is before the limits bite, but even over 18 months incomes will increase, allowing a bit more scope. Other factors—which can’t be quantified—will also impact, however, including whether banks allow high DTI lending up to the limits and whether borrowers find new ways to supplement deposits.

The post-lockdown experience was not your typical house price boom, which usually take place over five-plus years. The boom in the 2000s is probably a better example of a normal boom, in which the REINZ NZ House Price Index rose 116% from January 2001 to August 2007. Over the same period Statistics NZ’s estimate of average hourly earnings (which may understate total income growth) increased 24%.

To illustrate, let’s use a hypothetical example.

Let’s say, in 2024, a first home buyer with a gross annual household income of $100,000 were to buy a $600,000 house with an 80% mortgage—so they’re borrowing $480,000. In this scenario, the DTI is 4.8.

Now, let’s jump five years into the future.

Factoring income growth into the equation, how much would house prices need to increase over those five years in order for that same property—if it were purchased by the same buyer—to come in at a DTI of 6?

Let’s say incomes increased 20% over those five years—so, now, that same first home buyer has a gross income of $120,000. Using an 80% mortgage and a DTI of 6, that means they would be able to borrow $720,000 and buy the property for $900,000.

That’s a 50% increase on the 2024 price.

To put this in perspective, five years into the early 2000s house price boom, the REINZ NZ House Price Index had increased 87%. A 50% increase is 57% of an 87% increase.

How generous banks are in allowing high-DTI lending will be a big determiner of the impact on house prices. At face value, DTIs will stop a repeat of the post-lockdown mega-surge in prices and will (over time) bite enough to mean future major upturns in prices are considerably weaker than past ones, but increases could still be quite significant.

This is almost certainly so for the next one that should start in 2025 because the starting point for it is fewer high DTI loans than the limit allowed by the RBNZ.

By Rodney Dickens, Managing Director, Strategic Risk Analysis Ltd www.sra.co.nz.