Over the last few years, we’ve often talked (some might say “banged on”) about the need for greater levels of competition in the retail deposit market in New Zealand.

Today, for something a bit different, I thought I’d take a look at the other side of the coin—New Zealand’s home loan market—and explore how the space has evolved over the last five years, fostering more competition along the way.

At a macro-level, there have been some pretty significant changes to New Zealand’s mortgage industry in recent years

Specifically, the way home loans are “distributed”—i.e. how homeowners and potential homeowners go about sorting their mortgages—has shifted massively.

And those changes are playing out in a way that’s helping to keep banks' pricing competitive, at least relatively speaking, compared to what we were seeing in the market pre-2019.

Since 2019, mortgage advisers (or brokers, if you prefer) have increased the share of loans they manage from <40% to around 60% of the total market.

(It’s worth noting that not all banks disclose this information, so we’ve had to make some educated guesses as to the true number—but we’re pretty confident in the figure we’ve arrived at.)

The following case study demonstrates how the growing popularity of mortgage brokers is helping to drive greater competition among New Zealand lenders

The way New Zealand’s banking system works means that (most of the time) lenders price their home loan rates pretty much on par with one another.

But in early June 2023, ASB broke from the pack, pushing through increases to its six-month, one-year, and 18-month fixed term rates.

The biggest hike was to its one-year rate, which jumped from 6.78% to 7.04%—almost half a percent above what was on offer with most other major lenders—making it the only New Zealand lender with a one-year fixed rate above 7.00%.

To put the move into context… Just days before, the Reserve Bank had hit pause on rate increases (holding the Official Cash Rate at 5.50%) effectively signalling that we were at, or very near, the top of the cycle.

Meanwhile, wholesale rates—which are a key determinant of how banks set their mortgage rates—had been largely flat.

In other words, based on what was happening in the market, there arguably wasn’t a whole lot to support the increase

So, what was the thinking behind ASB’s decision? In short, it all came down to bank margins.

The move followed comments from ASB’s Australian parent company, Commonwealth Bank, that home loan interest rates were too low (relative to wholesale interest rates) to generate sufficient returns for the banks.

Bumping up mortgage rates was one way to address that.

Squirrel CEO, David Cunningham, wrote a rebuttal to these comments at the time ASB raised its pricing (parts of which were published in the AFR) outlining why the strategy was problematic.

ASB was relying on other banks following its lead, which would have pushed mortgage rate pricing up across the board

Although other lenders did increase their rates over time—in line with what was happening with wholesale interest rates—none quite matched ASB.

In the months that followed, ASB delivered two further rate hikes (in July and September 2023) in an attempt to lead the market further upwards.

As a result, Squirrel (and likely other advisors too) changed the advice we were giving to our mortgage customers

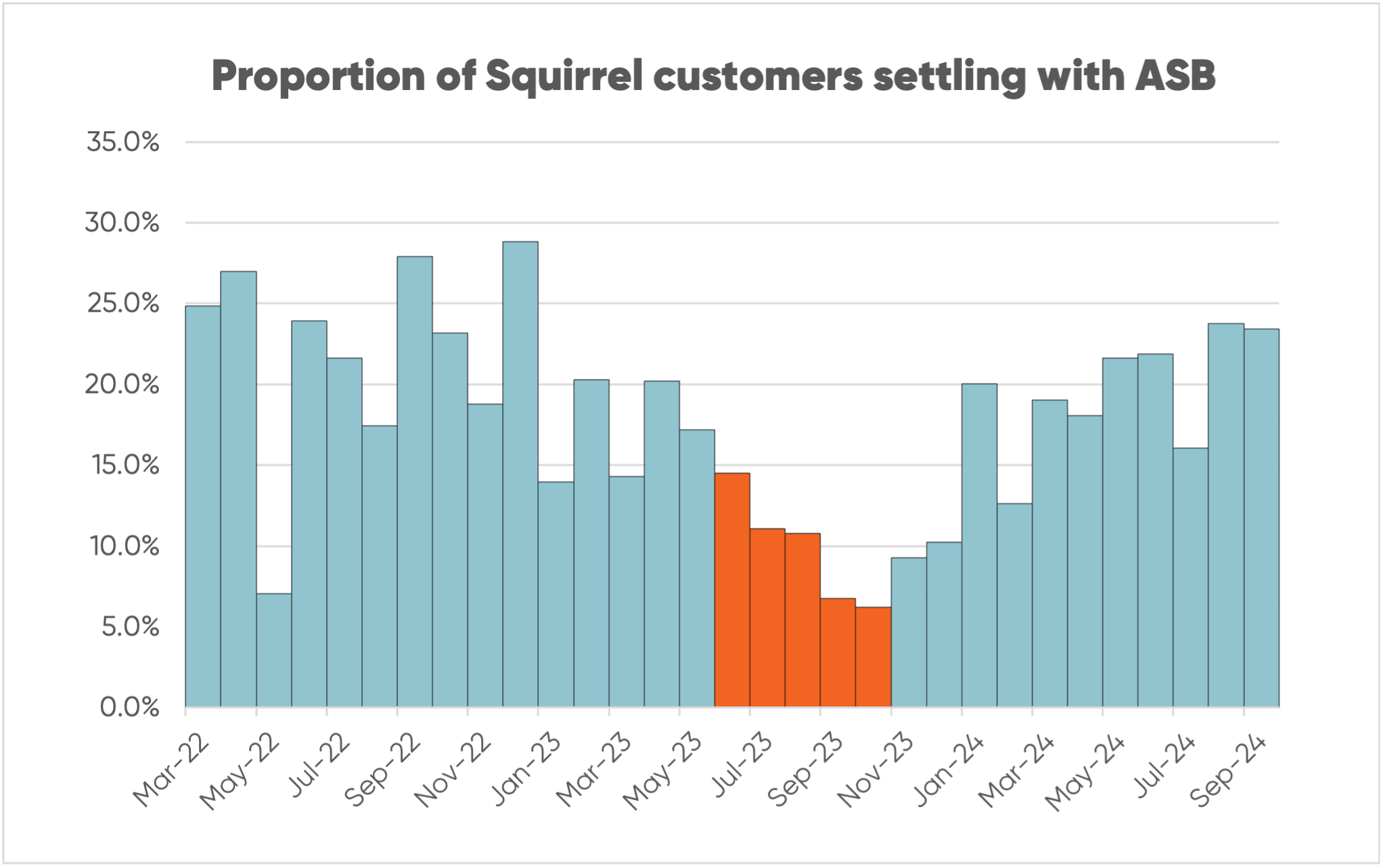

The graph below shows the proportion of Squirrel-advised customers settling a mortgage with ASB on a monthly basis.

The bars in orange represent the period from June 2023 (when ASB first increased its rates) to October 2023 (when it dropped them to be in line with the rest of the market).

Assuming that other mortgage brokers took a similar approach, ASB’s share of new business from brokers would have fallen from an average of ~20% down to near 10%, with some months as low as 5%*.

In other words, ASB’s market share would have fallen enough during this period to start damaging their profit lines

Remember that advisers are responsible for roughly 60% of new business going to the banks—and when you halve the number of sales you’re making through a channel that big, of course it’s going to hurt.

It’s reasonable to assume that the volume of new business ASB was writing direct through its branches also fell.

As other lenders hoovered up the business that might otherwise have gone to ASB, it become increasingly clear the approach was an unsustainable one.

So, eventually, ASB relented and returned its pricing to be in line with other banks.

There are two final points I’d like to make on this:

1. ASB could have been successful with its strategy had it increased its deposit pricing at the same time it increased its home loan pricing.

If it had started to grow its market share of deposits (i.e. savings) at the expense of other banks, then it’s possible ASB may have succeeded.

By failing to increase its deposit pricing, it made the move look like nothing more than a profit grab—and that didn’t resonate well with customers, or the market.

2. ASB (and its parent company) actually had a very valid point in that retail home loan rates were too low relative to where wholesale interest rates were sitting.

This is down to a structural problem in the market—whereby Kiwi get a relatively bad deal on their deposit pricing, which allows home loan pricing to be relatively cheap (although you might not think it) compared with wholesale interest rates.

Efforts to address this structural issue would create more fertile territory for other lenders to emerge in the home loan space.

Until this structural imbalance changes, we’ll continue to have a problem with home loan competition. I wrote more about this here.

* You might be wondering why, under the circumstances, Squirrel was still advising any customers to go with ASB. There’s a myriad of rational reasons why this would have been the case. One example might be because a customer had wider parts of their banking needs, e.g. their business, tied up with ASB and were somewhat locked in.