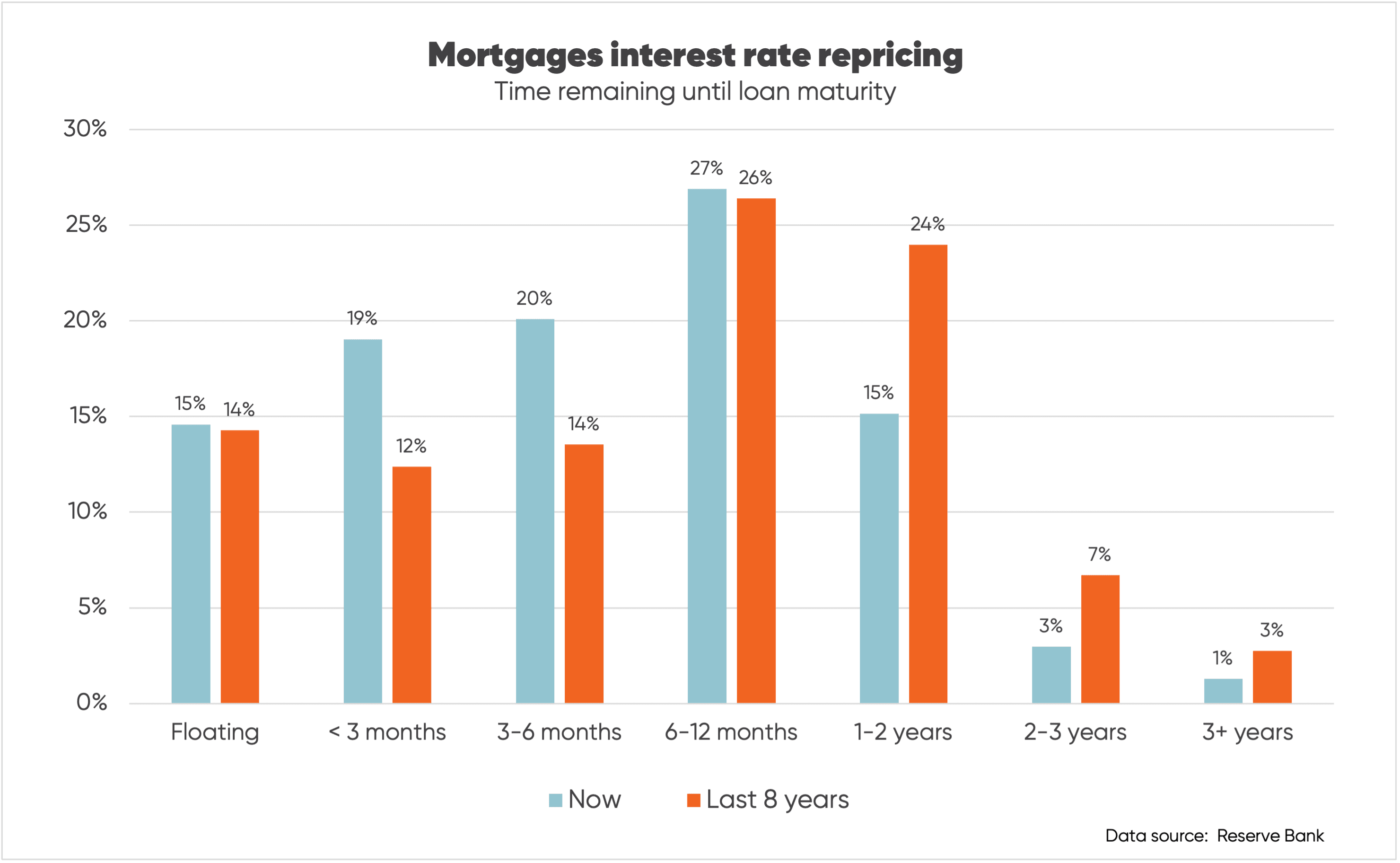

A whopping 80% of mortgages in New Zealand (as a proportion of our $370 billion in home loan debt) are headed for an interest rate reset sometime this year.

Of that, roughly 15% is on a floating rate, with the remainder made up of fixed-term loans due to mature within the next 12 months.

If you’re thinking “that seems high”, you’d be right.

Traditionally, the average percentage of loans either floating or maturing within 12 months has been somewhere around two-thirds of the market. So, I wouldn’t call it a tsunami, as such, but it’s certainly a king tide.

What does that mean for borrowers?

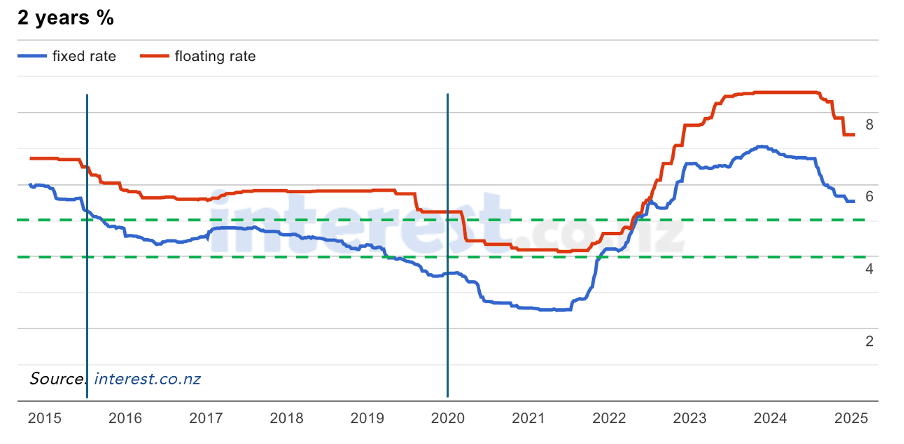

Today, the average interest rate Kiwi are paying on their mortgages is sitting at roughly 6.35%, up from 3% three years ago.

In dollar terms, that’s translated to a $10 billion increase in mortgage borrowing costs over the same period. An increase which has severely stunted household spending and economic growth, despite significant immigration and substantial pay rises.

(Incidentally, if you’re wondering why New Zealand is now in such deep recession, there’s your answer. Precisely what the doctor, Reserve Bank Governor Adrian Orr, ordered.)

But all that will start to unwind this year.

Most economists are picking a 0.5% Official Cash Rate (OCR) cut on 19 February 2025, with wholesale markets pricing a total of 1% cuts to the OCR, down to 3.25%, by September this year. That’s on top of the 1.25% of OCR cuts we’ve already had.

Of those heading for a reset in the next 12 months, there will be some (those savvy borrowers who locked in four or five years ago at around 3%) for which the change will be a massive shock, substantially increasing their interest costs. Granted, after a long time being spared the pain most households have endured.

For most, however, it’s good news. Assuming that market pricing is accurate, and the OCR will be down at 3.25% by September, that will almost certainly see mortgage rates for terms out to two years drop to sub-5%.

That will put about $4 billion back in homeowners’ pockets.

The importance of having a good interest rate strategy

A quirk of the mortgage market in New Zealand is that banks take very fat margins on floating rate loans.

Today, floating rates are sitting at about 7.4%, on average, compared to more like 6% on six- or 12-month fixed terms.

The difference is mainly banks feeding the fat margins at the trough (incidentally, something the Commerce Commission’s Market Study into Retail Banking Services should have addressed but didn’t).

It’s why, generally speaking—unless it’s only for a small portion of your loan, or for a very short period of time (say, less than two months)—you’re almost always better off fixing instead of floating.

In late 2024, however, we had one of those rare moments where floating became the recommended course of action for borrowers.

With interest rates tracking downwards already, and further cuts on the horizon, mortgage brokers were advising their clients to take a floating rate for a few weeks, then fix after the November OCR review, enabling them to lock in at a better rate.

In the last few months of the year, up to 50% of new mortgages were settling on a floating rate—more than double the usual 20%.

Where to from here?

Squirrel’s view is that, once we’re back at an OCR close to 3%, mortgage rates should settle near the top of the 4% to 5% band which is the range of the popular two-year fixed term for most of the five years before COVID-19.

Everyone’s financial circumstances are different, but once home lending rates are below 5%, it would be worth considering locking in for a longer term. As always, it’s important to seek personal advice from your mortgage adviser before deciding on the mortgage strategy that’s right for you.

The flip-side – depositors

There’s no way to sugar-coat it. If you’ve got savings, the OCR cuts are bad news.

The only bright star (which won’t last) is that banks are currently paying 5% for six-month term deposits. That’s very unusual, given that wholesale six-month rates are below 4%.

It’s quite likely that term deposit rates will all fall below 4% within six months.

For call accounts, the story is even worse. Today, banks are, on average, paying below 3.5% on savings accounts, with some offering as low as 2%.

Those rates, too, will drop with the forecasted OCR cuts.

Squirrel regularly updates our analysis of the best and worst bank savings accounts to help Kiwis compare and navigate their options.

If you’re keen to look at some alternatives, now could be a good time to consider Squirrel’s savings and investment products or alternative saving products offered by a number of Kiwi fintechs.