In a nutshell:

- ANZ has quietly lifted its floating home loan rate by 0.10% (but left their retail deposit rates unchanged).

- Across its floating rate home loan portfolio of $12 billion, that equates to an extra $12 million in profit each year.

- In the absence of a change in the Official Cash Rate (OCR) or funding costs, ANZ’s rationale for the increase really boils down to “because we can”.

- Word on the street is that the move is to help fund the cost of its recent 1.5% cashback offer for new home loan customers, which turned out to be far more popular (and therefore expensive) than anticipated, with many Kiwi refinancing their loans to get *free money*.

- This is classic oligopoly behaviour: punish existing customers to fund winning new customers.

- For existing customers, our advice is to play the game. When these sort of cashback offers are available, look at switching banks and earning the cashback.

ANZ lifts its floating home loan rate just because...

In a pretty blatant show of audacity, ANZ has this week announced increases to its floating and flexi mortgage rates:

- ANZ floating rate: up from 5.69% to 5.79% (effective 15th January for new customers and 29th January for existing)

- ANZ flexi rate: up from 5.80% to 5.90% effective 29th January

The reason ANZ has given for the move? It’s "…a small change to our floating and flexi rates to align with market conditions".

So, what are those market conditions exactly?

Answer: Most other banks’ floating rates were higher, so they could lift their own!

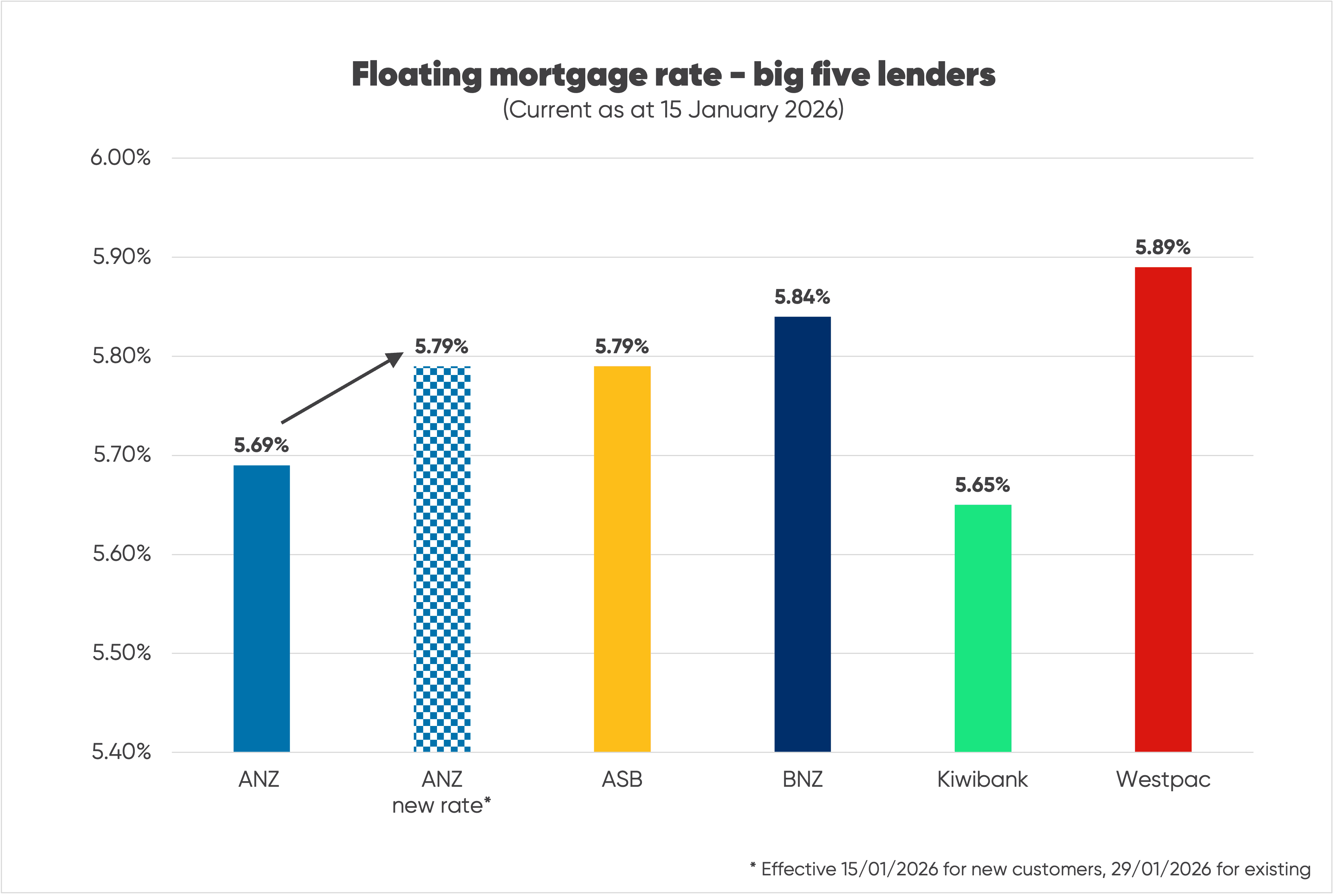

Here’s the picture:

Prior to the move, ANZ’s floating rate was essentially caught in no man’s land between Kiwibank and other major lenders i.e. it wasn’t the cheapest, but it wasn’t the most expensive either.

That meant there was no competitive advantage to leaving it where it was, so it’s chosen to go down the revenue optimisation route instead.

How do banks decide where to set their interest rates?

Each bank has a Pricing Committee that meets on a weekly basis.

The Committees’ job is to look at the big picture of what’s happening across the industry—taking into account things like competitor deposit and loan interest rates, wholesale interest rates, loan demand, deposit flows, special offers and profit measures—and set pricing accordingly.

Because New Zealand’s banking sector is an oligopoly, the two main considerations at play are:

- What competitors are doing (which is why interest rates across the major banks tend to be so similar)

- And profitability—because at the end of the day, banks’ main objective is making money for their shareholders, and more than 80% of New Zealand’s retail banking market is controlled by the Australian banks.

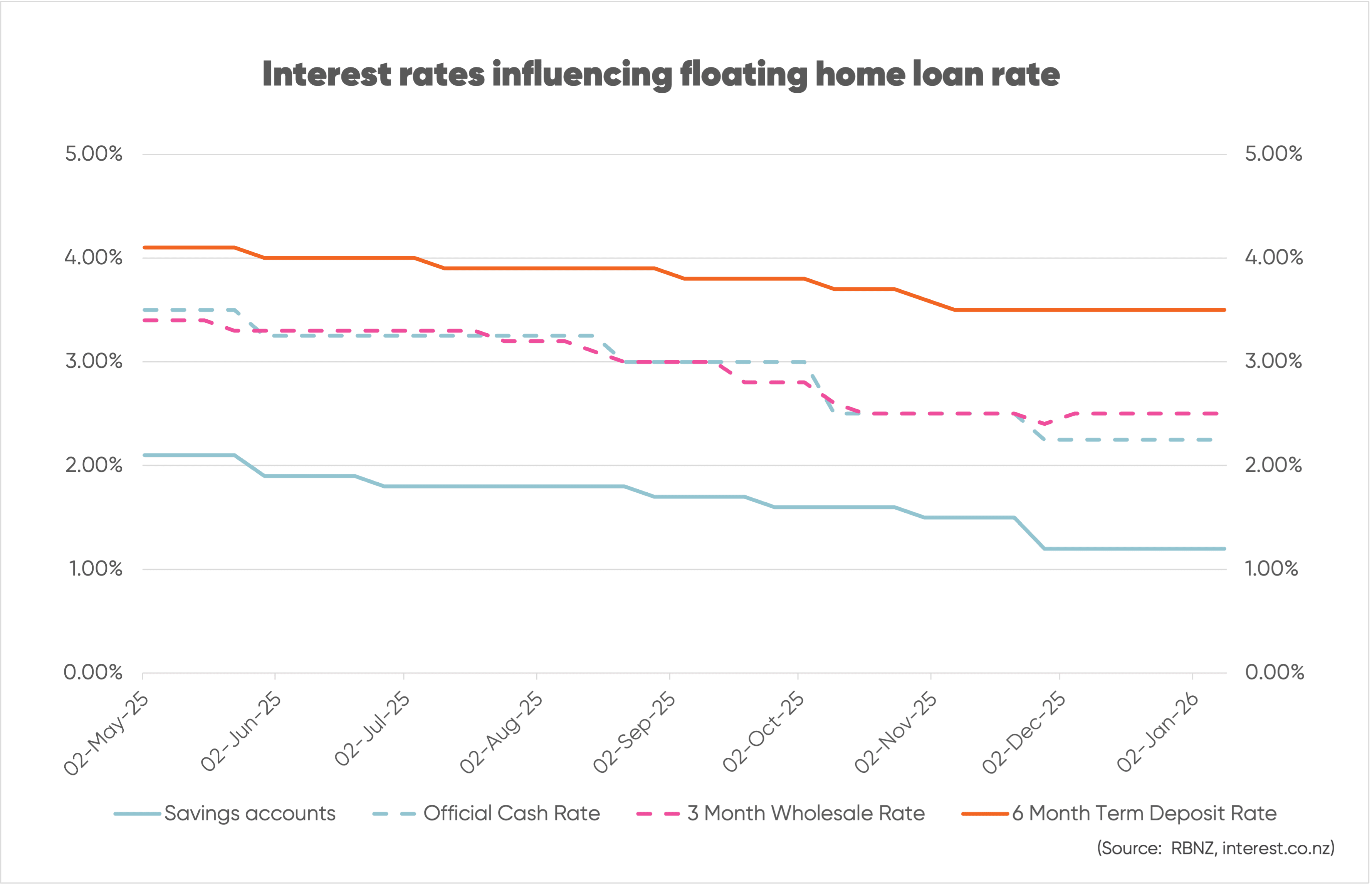

Of course, what’s happening with interest rates also makes a difference—with the main influences being movements in the OCR, shorter-term wholesale rates, term deposit rates, and savings account rates.

But not this time.

As you can see in the chart below, all those major rate influences have remained unchanged since ANZ last adjusted its floating home loan rate just after the OCR review on 26 November 2025:

So that “alignment with market conditions” clearly just means aligning with competitors at a higher level.

Why the sudden profit grab?

Late last year, in the hopes of growing its mortgage lending book, ANZ ran a campaign offering 1.50% cashbacks to new customers.

It was an insanely compelling offer—the largest cashback we saw at Squirrel was over $30,000.

So compelling, in fact, that (in our view) it’s likely ANZ thought none of the other banks would be prepared to match it.

As it turned out, most did—with the net result being a frenzy of bank switching, where existing mortgage customers jumped ship and took their loans elsewhere simply to get the cashback.

Now, when the banks decide to go big in their efforts to attract new customers, you typically get one of two scenarios:

- The offers stimulate activity and effectively grows the market.

- Or, as in this case, there is next to no additional growth, just a whole lot of movement. With all other things being equal, bank profits are lower, and lenders end up having to find other ways to subsidise the offer.

In this case, what ANZ got was a game of customer pass-the-parcel, and every customer who played the game won (in the form of huge cashback).

To recover this, we estimate that fixed and floating home loan rates are 0.1% to 0.2% higher than they would otherwise be.

In short, the sweetheart deals were funded by existing customers.

After finding itself swamped with cashback payouts, ANZ has now chosen to recover some of the cost by raising its floating home loan rate.

With interest rates expecting to stay largely flat over the course of this year, it’s essentially just a move to lock in a fatter margin.

Is this fair?

Short answer, no. But it’s how oligopolies work.

Ever noticed that petrol prices are essentially the same across each brand? That the same tools cost the same at Mitre 10, Bunnings and Placemakers? That electricity prices are little different between suppliers?

Of course, there are ‘specials’, especially for new customers, but it’s existing customers who ultimately subsidise them.

As Antonia Watson, CEO of ANZ in New Zealand, said on the Mike Hosking’s Breakfast show on 11 November 2025:

“…If someone puts rates down, others will follow. That’s a very competitive market. But the suggestion there is once everyone matches us, we should continue putting them down, and then everyone matches and continue putting them down, and then there comes a point that it’s unsustainable, and we don’t therefore have the returns that mean that we’re comfortable to keep lending to Kiwis…

…do we want a vicious cycle to the bottom, well that will mean we have less strong and stable and sustainable banks.”

Paraphrasing this:

“In an oligopoly, there’s little point in competing too hard because no one wins and everyone loses.”

Unless you’re the customer, of course—in which case you’re losing either way.

As a customer, the best strategy is to play the game. When these sorts of cashback offers are available, look at switching banks and earning the cashback.

Footnote:

The banking oligopoly is the reason floating home loan interest rates across the major banks are 5.79%, while their one-year fixed mortgage rate is 4.49%.

In rough terms, relative to funding costs for the different terms, that’s an extra 1.3% of margin.

With about $40 billion worth of home loans in New Zealand sitting on a floating rate, that means the banks are creaming over $500 million excess profit each year.

Simply because they can.

About the author: David Cunningham, Chief Squirrel

With more than three decades of senior experience across New Zealand’s financial services sector, David knows the world of banking and finance inside out. He's not afraid to call it like he sees it (all part of our fight for a fairer financial system) which is why he's a regular media commentator on matters relating to the economy, housing market, mortgages, saving and investing, and interest rates.